How Book Lovers Organize Their Shelves

Notable locals share strategies and setups anyone can take a page from.

TEXT BY VIRGINIA M. WRIGHT

Photos by Dave Waddell

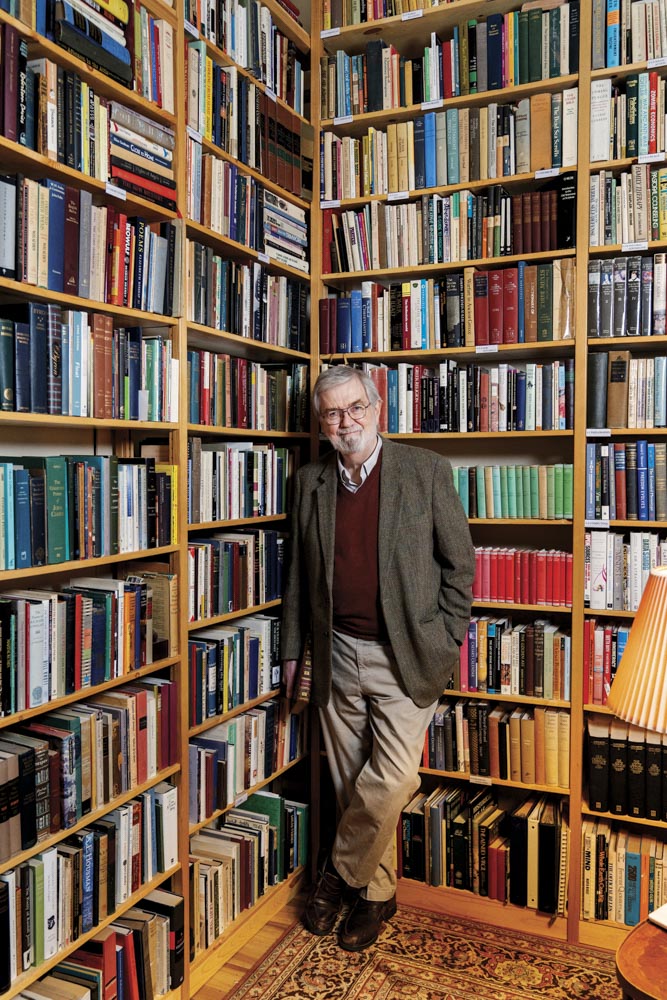

Mind Map

Author and maritime historian Peter Neill says that he’ll never count his books, but he did measure the size of his collection once, when he and his wife, artist Mary Barnes, moved from New York City to Sedgwick 20 years ago. Blue Hill architect Bruce Norelius used that spec — about 128 linear feet — to configure the floor-to-ceiling birch-veneer shelves in Neill’s office/library. “When we unpacked the books, the fit was almost perfect,” he says. “I put my tchotchkes and memorabilia in the extra space.” Neill calls his shelves a “map of my brain.” Books are grouped by theme, and each transitions logically, more or less, from one to another: nautical books merge with oceanography ones, which merge with nature and environmental essays, which merge with collectible books about nature and travel, which merge with American and European first editions, which merge with literary mysteries and thrillers. With a wall of glass offering a distant view of Eggemoggin Reach, the room is a brighter version of the dark-wood, book-enveloped study Neill has dreamed of since he was a boy. “Every morning, I jump up and come in here, and I’m here at the end of the day too. There’s always something to do.”

Advertisement

Photos by Dave Waddell

Good Compromise

Charlotte Crowder calls husband Mark Shaughnessy “my book club” because they often read the same titles. Their tastes diverge, however, when it comes to organizing the collections in their Brooksville home. Crowder, a medical writer and author of the children’s book A Fine Orange Bucket, likes to shelve volumes by their authors’ country of origin. Shaughnessy, a business professor at Maine Maritime Academy, prefers grouping by topic and size. So they compromise. Most fiction is arranged her way. North American authors, for example, occupy their birch bedroom bookcase, one corner of which Blue Hill contractor Larry Packwood fashioned to tuck neatly under the slanted ceiling. Shaughnessy prevails with nonfiction and children’s books, which inhabit shelves built into the second-floor landing’s half-wall. Their organizational preferences blend in the living room, where full sets of books by Dickens, Thackeray, Goethe, and Schiller are neighbors. Keepsakes, like an 1872 leather-bound edition of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare and a 1758 German prayer book with brass closures mingle with them. “There are never enough bookcases,” Crowder finds. “I don’t part with books, and the name of anyone who borrows a book from me is emblazoned in my head until it comes back.”

Photos by Tara Rice

Reading Refuge

Nicole Beaulieu’s spirit is palpable in the library of Michael Macomber’s Saco Federal. The couple was married here in the early days of the 2020 pandemic lockdown, when Beaulieu was fighting cancer, a battle she lost a few months later. A photo of their wedding rests on the large sage-green bookcase the couple designed with Biddeford furniture maker Gabriel Keith Sutton, who crafted the molding to match that of the room. Macomber, the owner of Biddeford’s Elements bookstore and café, groups books into fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, but sets aside “those that have meaning for me and those that had meaning for Nicole.” Next to the wedding photo is Macomber’s first gift to her, Time by Andy Goldsworthy. Here too Beaulieu peers upward from a picture frame, her gaze seeming to rest on Wade in the Water by her favorite poet, Tracy K. Smith, on the shelf above. Macomber pays homage to his abandoned doctoral dissertation with a set of books by the third Earl of Shaftesbury, an 18th-century English philosopher. Presiding over his comic-book collection is a figurine of Scarlet Witch, a character from the miniseries WandaVision, which he watched after Beaulieu’s death. “To my surprise, it was all about grief. It helped, but it hit hard.”

Advertisement

Photos by Tara Rice

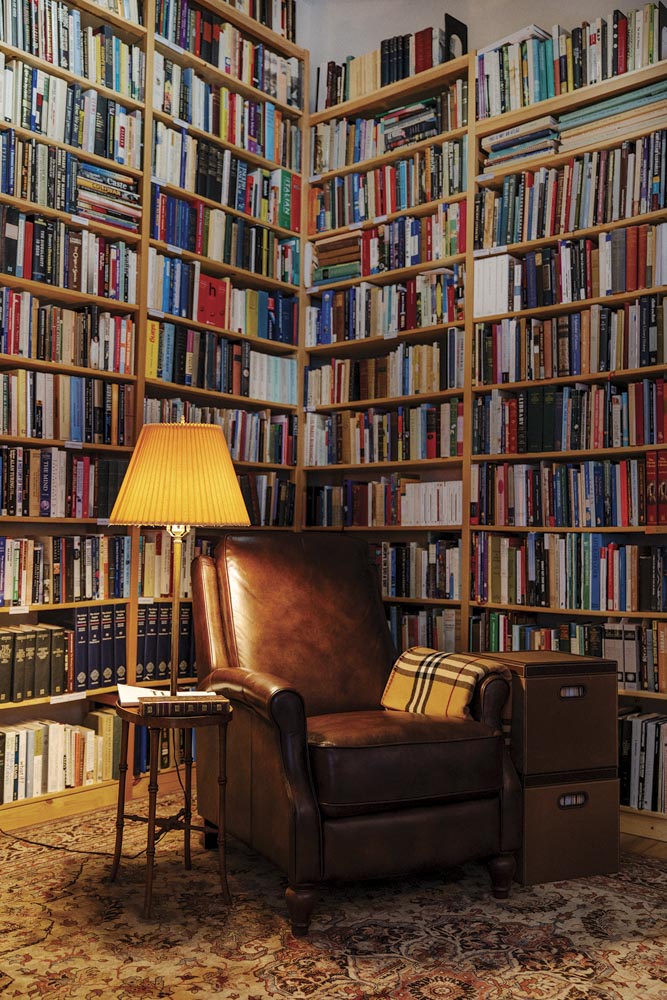

“Book-Wrapt”

In The Private Library, author Reid Byers coined the term “book-wrapt” to describe the warm elation of being enveloped in a roomful of books. “All libraries are magical rooms,” he wrote. “All their windows look out onto Faërie, and all their carpets can fly.” Three years ago, Byers acquiesced to his wife Patty’s desire to move from their five-bedroom Shingle-style house in Farmington to a Portland condo on the condition that he keep his 5,000–6,000 books. His collection, separated into fiction by author and nonfiction by subject, sprawls over three rooms outfitted with 12-foot-tall pine bookcases. He uses a ladder to reach the top shelves. “It’s awkward because you can’t browse, but it still gives that feeling of satisfaction,” Byers says. Only a room set aside for collecting books can feel book-wrapt, he believes; individual stacks scattered throughout the home don’t have the same impact. “Over the years, I’ve found that if you start someplace in the room, pull a book off the shelf, put it back, pull the next one, put it back, in 10 minutes you will find something you didn’t know you had, and it will keep you fascinated and happy for hours.”